Flag it?

Out, damned spot! Out, I say!—One, two. Why, then, ’tis time to do ’t.

Lady MacBeth in ‘MacBeth’ (Act 5, Scene 1) – William Shakespeare

One of the main arguments put forward in favour of a flag change for New Zealand is that it represents an opportunity to ditch the presence of the Union Jack on the flag.

That presence – for many people – represents a symbol of New Zealand’s continuing inability to stand proud, on its own two feet (i.e., have its own version of nationalism rather than a borrowed one). Relatedly, for some sub-set of those people it represents a tacit ‘bending of the knee’ to an old, and now defunct, colonial power and an implicit endorsement of colonialism itself, including its undeniable brutality and injustice.

The most disturbing connotation is the second.

Like Lady MacBeth’s obsessive hand washing aimed at removing the bloody mark of murder on her hand the Union Jack – for some in the flag change camp – represents an indelible bloodstain on New Zealand’s flag that needs to be scrubbed clean from our national symbology at any cost.

There are, then, two threads to the argument for the Union Jack’s removal from the flag: (1) The need to create an independent identity and (2) the moral obligation to remove any tacit reminders of, or approval for, colonialism and empire.

As I said at the end of Part I of this post, serious stuff.

Those threads are related and each individual who opposes the presence of the Union Jack on the flag no doubt combines them in different ways. Together they make probably the most powerful argument for change.

I’ll take each thread in turn.

Identifying Identity

One fairly simple truth about the modern nation state of New Zealand is that it only exists as a product of British imperialism and colonialism – just as these islands themselves only exist because of the impact between two continental plates. Both processes could be brutal, bloody and cruel but, respectively, they’re the reasons that this nation state and this land exist.

That’s also of course why the Union Jack got on the flag in the first place.

So that’s the first point: Colonisation and imperialism is the truth about this nation’s origins. I think most people who have strong views on the flag referendum – either way – would accept this point.

But should it still be the nation’s ‘identity’? If not, shouldn’t the flag represent our ‘new identity’?

Who, it might be asked, still ‘identifies’ with those colonial origins?

Aren’t we ‘beyond’ them today? Isn’t New Zealand a ‘very different society’ from when people used to refer to Britain as ‘home’? Don’t we now ‘identify’ with something other than the colonial past? Shouldn’t we be ‘looking forward’, into the future to what we can be and not focus on what we once were?

Good questions. But here’s one I want to focus on: Can a nation’s identity be voted on?

Can it be chosen? And is that choice limited only by our imagination or a ‘dare to believe’ attitude?

Importantly, we’re not – or we shouldn’t be – talking about each individual’s ‘identity’.

Individuals can identify with whatever they choose – for good or ill; wisely or foolishly. But can individuals choose a ‘national identity’ and then represent it on a flag?

There are two words that it might help to define here. A ‘country‘ is generally accepted to refer to some political arrangement – usually a sovereign state:

A country is a region that is identified as a distinct entity in political geography. A country may be an independent sovereign state or one that is occupied by another state, as a non-sovereign or formerly sovereign political division, or a geographic region associated with sets of previously independent or differently associated people with distinct political characteristics.

By contrast, a nation can sometimes refer to a ‘people’ who have lived as a community for some time and developed a “cultural-political community“. A nation:

is a social concept with no uncontroversial definition, but that is most commonly used to designate larger groups or collectives of people with common characteristics attributed to them—including language, traditions, customs (mores), habits (habitus), and ethnicity. A nation, by comparison, is more impersonal, abstract, and overtly political than an ethnic group. It is a cultural-political community that has become conscious of its autonomy, unity, and particular interests.

Importantly, it is ‘impersonal’ because it serves to unite strangers (who may never meet) into an ‘imagined community’. Typically, today that ‘imagined community’ is a nation state.

Flags – fundamentally – represent nation states. And nation states are very different from the beliefs a population of such ‘strangers’ might individually have about themselves. They are ‘cultural-political’ constructs. Nothing more, nothing less.

The reason I ask these questions (about voting on national identity) is that, as many have pointed out, there is no obvious, tangible reason why the question of changing the flag should be asked – or answered – at this time.

That means there’s no agreed upon reference point to which the design of a new flag could be addressed.

Untethered from any such unequivocal and broadly accepted ‘trigger’ much of the reasoning for a flag change revolves around certain claims about ‘national identity’. Yet how does a flag represent some new ‘identity’ that, it seems, at least part of the population ‘sense’ has arrived? And how do we determine just what newly sensed ‘identity’ a new flag should represent?

Does each of us simply shout the loudest so that our version of New Zealand identity gets picked? Is something like national identity reducible to a counting exercise and whoever gets the most ticks gets to claim a particular ‘identity’ for New Zealand?

By comparison, other nations had it easy: Because their changes in flag marked some clear shift in the character or status of their nation state (its founding, a revolution, a constitutional change, the incorporation of new lands and people, etc.) it was more obvious what a changed flag should henceforth be required to represent. (Of course, just how such changes should be represented could still be debated but there was usually general agreement on the more or less objective change that the new flag should represent.)

[There is one exception that I know of: the Canadian flag change – more on that later but it amounted, as much as anything, to what should not be represented in order to paper over some internal tensions.]

When, for example, South Africa shed the apartheid system it was clear what a new flag needed to represent: The equality of all people in the new nation (that was the entire ‘moral force’ behind the shift in the nation’s constitution). Hence the ‘rainbow’ flag:

Flag of South Africa since 1994

The explanation of the colouring makes clear the intent at equality and unity:

Three of the colours – black, green and yellow – are found in the banner of the African National Congress. The other three – red, white and blue – are displayed on the old Transvaal vierkleur (which also includes green), the Dutch tricolour and the British Union flag.

As an aside, any reference to the ‘British Union Flag’ on the new South African flag is a surprise given the horror of British actions in South Africa during the so-called Boer War. But there you go (and, once again, more on that later).

A similar focus on unifying distinct groups – i.e., a new ‘cultural-political’ arrangement – can be seen in the design of the Irish flag:

Flag of Ireland

Once again, the colours tell the story:

The Irish government has described the symbolism behind each colour as being that of green representing the Gaelic tradition of Ireland, orange representing the followers of William of Orange in Ireland, and white representing the aspiration for peace between them.

[The tricolour design may also have been inspired by the revolutionary French flag – the flag so famous that it goes by the name of the design: The Tricolour.]

It is so much harder when there is no natural agreement on what a supposed or claimed incremental and evolving change in identity has or has not amounted to. Even if there were a steadily growing sense that ‘we are different now’ in the New Zealand population and even if that ‘difference’ were universally seen as a positive difference that needed expression in a new flag there’s still the fundamental problem and question of ‘Different in what way?’

The intangibility of the bare notion of a shifting ‘identity’ – unsupported by any clear change in national status or orientation in the world – is a recipe not only for conflict, divisiveness and rancour but also for a national vagueness and depthlessness that could easily slip into self-delusion and fantasy.

And facts, inevitably, will get in the way of some preferences concerning ‘our’ identity that some of ‘us’ might hold dear. Despite what motivational self-help books might implore us to believe, reality has a habit of mocking our untethered fantasies about ourselves (in some cases, quite literally – here and here).

But we’re now stuck with trying to make a choice in just such an amorphous context. There is no guidance from some constitutional change, no hint from some explicit shift in national status. So how do we anchor our choice of flag in such unpromising circumstances?

I can only see two islands of relative solidity in this sea of murk: The truth about New Zealand’s past and the truth about New Zealand’s present. And, since we are talking about a national flag ‘New Zealand’ here refers to the political entity of the nation state not to any mythic ‘identity’.

‘Truth’, as they say, is a contested concept but at least it references something more than ‘hopes’ and ‘aspirations’ – which could be absolutely anything.

Flags, it’s worth remembering, are not usually or principally expressions of this strangely modern notion of ‘identity’. For example, what ‘identity’ – in the sense so many are using the word in the present debate – does the stars and stripes or the Union Jack/Flag represent? How, in its design terms, do thirteen stripes and 50 stars represent ‘home of the brave’ or ‘land of the free’ or ‘truth, justice and the American Way’? How do three overlain crosses of Saints represent ‘stiff upper lips’, understatement and toilet humour?

They don’t.

Instead, they are – quite appropriately, being national symbols – expressions of political realities and arrangements. Crosses on flags come from political arrangements involving the Christian Church. Tricolours represent, through their colours, combinations of peoples in one political unit. The Pan-Arab colours represent moves towards a ‘United Arab Republic’. Green (in some flags) represents allegiance to Islam. The presence of crowns on flags represents monarchies.

Flags generally only represent ‘national identity’ to the extent that such political realities and arrangements come to be fused into that broader identity. Given time, any flag can of course come to be used to express that broader identity but that’s incidental to the design.

And, sometimes, the particular versions of ‘national identity’ (or nationalism) a flag gets used for may not be one that everyone in that nation state have signed up to – think of the St George Cross as used by the National Front in England.

Modern nation states are, first and foremost, political units (that’s why ‘border disputes’ are so common). Given that, the question becomes ‘What are we as a nation in this world?’.

What are the political realities and arrangements of the modern New Zealand nation state? That is, where does New Zealand stand in that web of connections and relationships that constitute the ‘family of nations’?

If the flag truly is this ‘important symbol’ (which is supposedly why it is so vital that we change it) then shouldn’t such an important symbol actually represent the truth about this country? Shouldn’t it represent the reality – past and present – of those arrangements?

Yes, flags can express ‘aspirations’ or ‘hopes’ (e.g., that the ‘Green’ and ‘Orange’ people of Ireland might live in peace) – but there’s a fine line between ‘aspiration’ and self-deceit. That line becomes more and more blurred the greater the discussion descends into the ‘values’ and moral preferences that symbols like national flags should represent.

One of the reasons I’m not keen on nationalistic symbols is that they typically err on the side of self-deceit. They are part of a ‘mythology’ (in the worse sense of the word) that has as its main aim the avoidance of the truth rather than simply its optimistic, positive and hopeful expression.

Put bluntly, just saying that something is so doesn’t make it so.

Just saying that New Zealand is an independent, multicultural land of peace – as Kyle Lockwood claims his flag design depicts – does not, I’m afraid, make New Zealand an independent, multicultural land of peace:

Designer’s description

The silver fern: A New Zealand icon for over 160 years, worn proudly by many generations. The fern is an element of indigenous flora representing the growth of our nation. The multiple points of the fern leaf represent Aotearoa’s peaceful multicultural society, a single fern spreading upwards represents that we are all one people growing onward into the future. The bright blue represents our clear atmosphere and the Pacific Ocean, over which all New Zealanders, or their ancestors, crossed to get here. The Southern Cross represents our geographic location in the antipodes. It has been used as a navigational aid for centuries and it helped guide early settlers to our islands.

In some ways the choice of flag may well come down to staying with a more or less accurate, though unflattering, representation of New Zealand or a polite ‘Janet and John’ wistful representation of earthly paradise.

The really disappointing aspect of the entire flag change referendum and process is that we have not had any public discussion of the substantive political questions that should provide the answer to how the nation state – the country – of New Zealand is symbolically represented in its national flag.

Instead, we’ve gone straight to the ‘Which one do you LIKE?’ phase.

Imagine a discussion in which we could have debated whether or not our colonial past should be acknowledged in a flag and, if so, how and through what symbology?

Imagine considering the extent to which we might want to make connections with our land, with neighbouring countries (Australia, the Pacific Islands, Asia)?

Imagine discussions about the constitutional cornerstones a flag should represent – through its colours, perhaps – or maybe through allusions to democracy or the rights and importance of the people (us) in this country?

Imagine finally addressing, through the symbol of a new flag, the way in which the treaty partners reside together here? (Not unlike how that is acknowledged in the New Zealand Coat of Arms).

By way of contrast to the opportunities such a discussion would have provided the responsibilities the Flag Consideration Panel were given when established say nothing of these kinds of matters.

Those responsibilities were entirely focused on process:

Panel members

The members of the Panel were nominated by a cross-party group of Members of Parliament (MPs) and appointed in late February [2015]. They’re responsible for making sure that the flag referendums process is:

- independent

- inclusive

- enduring

- informed

- practical

- community-driven

- dignified

- legitimate

- consistent.

Then, as part of the consideration process, there was a massive qualitative analysis of the sorts of ‘values’ people expressed at the workshops, on social media, via the website, etc.. This led to the following ‘word cloud’:

Source: https://www.govt.nz/browse/engaging-with-government/the-nz-flag-your-chance-to-decide/how-we-got-here/our-common-values-considered/

More prosaically, the words were:

What you shared informed the Panel

Large words:

- freedom

- history

- equality

- respect

- family

- heritage

- present

- future

- kiwi

- integrity.

Medium-sized words:

- commonwealth

- peace

- māori

- green

- pride

- honesty

- love

- environment

- past

- unity

- unique

- tradition

- fairness

- british.

Smaller words:

- community

- culture

- free justice

- democracy

- clean

- equal

- united

- fair

- independence

- beautiful

- independent

- caring

- helping

- opportunity

- pacific.

Yes, a ‘word cloud’ was the simplification, the distillation of what could have been a far more substantive discussion.

It’s like using free word association – ‘What do YOU think of when you hear the words ‘New Zealand’?’ – to tap the ‘inner psyche’ of the nation. What would have been wrong with deliberately and publicly addressing specific questions about the kinds of political arrangements that underpin, or that we intend to underpin, the New Zealand nation?

Rather than addressing these substantive questions we ended up with a list of ‘feel good’ adjectives. They might make our chests swell with pride but, really, who do we think we’re kidding? I’m surprised ‘motherhood’ and ‘apple pie’ (or perhaps the more ‘indigenous’ pavlova) didn’t make an appearance on the list.

According to the Panel, these values (really just platitudes) informed their shortlisting in the following ways:

In reviewing flag designs, first and foremost, we were guided by what thousands of Kiwis across a range of communities told us when they shared what is special to them about New Zealand. This provided the Panel, and flag designers, with valuable direction as to how New Zealanders see our country and how those values might best be expressed in a new flag.

The message was clear, and the Panel agreed. A potential new flag should unmistakably be from New Zealand and celebrate us as a progressive, inclusive nation that is connected to its environment, and has a sense of its past and a vision for its future.

They were ‘guided’ by our submissions. I’m sorry but if these vacuous snippets pasted into a word cloud were the signage they used to guide them to a ‘vision of New Zealand’s future’ then that explains the quality of the output.

As a reminder, here’s the four short-listed flags that were chosen for the first referendum (I leave Red Peak out since it didn’t come from the panel’s deliberations):

The flags that should “unmistakably be from New Zealand and celebrate us as a progressive, inclusive nation that is connected to its environment, and has a sense of its past and a vision for its future.”

I suppose the omnipresent fern represents connection to the environment (as could the blue in the Lockwood flags – for the sea – and the Southern Cross – for the night sky). Unmistakably from New Zealand? Maybe the black colour, although black is on many flags.

‘Progressive’ and ‘inclusive’? Now I’m lost. Perhaps the koru? Unfolding represents the future potential, I guess, and even ‘progress’ in the sense of growth. A completely unfolded frond doesn’t really have much more to do than shed its seeds and go brown so I’m not sure if that counts as ‘progressive’ symbology.

A ‘sense of its past’ – well the bits taken from the old flag in the Lockwood designs would fit that; not sure where that sits in the other two. ‘Vision for its future’? Again, maybe the koru.

As for the ‘Large Words‘ like ‘family’, ‘equality’, ‘respect’, ‘integrity’ and ‘freedom’ it would take a more imaginative narrative than I’m capable of weaving to extract those values from any of the four designs.

Let’s be honest. The flag consideration process was less a process of consultation over an important constitutional symbol than it was a marketing exercise with the aim of summarising what buzz-words about their country appeal to New Zealanders.

Word clouds are all very nice to look at in powerpoint presentations – and they can even validly help to summarise a large textual dataset. But they are only the starting point for extracting meaning – not the endpoint. They should be used to go back into the ‘data’ – the comments, conversations, emails, etc. – and find the contextualised meanings and concerns that house these words.

Gutted of the narratives they were presumably originally embedded in how on earth could they guide the Panel’s ‘consideration’ of the flag designs submitted?

Look again at the ‘Large words‘: ‘History’, ‘Heritage’, ‘Present’, ‘Future’, ‘Kiwi’, ‘Integrity’, ‘Equality’, ‘Family’, ‘Freedom’, ‘Respect’.

What is our ‘Heritage’? What is it to be a ‘Kiwi’? What part of our ‘Present’? Of our ‘History’? What vision of the ‘Future’? ‘Equality’ of what? ‘Respect’ for whom?

There’s little in the way of logic that I can divine in the process to determine alternative flag designs that might represent New Zealand’s elusive ‘national identity’.

Ultimately, I don’t blame the Flag Consideration Panel for that. Detecting a coherent, let alone discernible, account of national identity via Facebook, emails, page views and – despite being “in line with best practice commercial principles” – a poorly attended series of public workshops was always going to be the proverbial up-hill job. Unfocused, disconnected and disjointed chaos – no matter how ‘inclusive’ – is in no way the same as ‘consideration’.

I suppose the process could be called ‘creative’ in the same sense that the ‘creatives’ in episodes of ‘Mad Men‘ lock themselves in a room over the weekend with nothing but each other and hard liquor to come up with some edgy ad campaign to sell cars, cosmetics or fast food.

Claiming that a flag expresses – or should express – national identity is folly and going in search of an emerging, new identity to help with flag design is a fool’s errand.

A more modest, and far simpler, role for a flag is, as I’ve argued, to represent some important political arrangements and realities.

So, in that sense, what is the ‘reality’ of this nation? What are the important political arrangements and realities that the ‘state we’re in’ manifests?

To answer that question I now need to follow the other thread, the one that sees in the presence of the Union Jack not just an outdated ‘identity’ but a symbol of some of the most egregious horrors committed around the globe over the course of centuries.

Jack of all flags?

Whatever overall judgment anyone comes to about the legacy of the British Empire there’s no doubt that its history is stacked to the gunnels with oppression, violence, brutality, considerable cruelty, racism and bigotry, and injustice on a global scale. And ‘gunnels’ it usually was as much of Britain’s power rested on its naval capacity.

If you’re in any doubt, here’s what Winston Churchill had to say about the Bengal (Indian) famine of 1943:

I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.

…

Winston Churchill, the hallowed British War prime minister who saved Europe from a monster like Hitler was disturbingly callous about the roaring famine that was swallowing Bengal’s population. He casually diverted the supplies of medical aid and food that was being dispatched to the starving victims to the already well supplied soldiers of Europe. When entreated upon he said, “Famine or no famine, Indians will breed like rabbits.” The Delhi Government sent a telegram painting to him a picture of the horrible devastation and the number of people who had died. His only response was, “Then why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

And if you want more on one of the most openly cruel British imperialists, here he is again:

The young Churchill charged through imperial atrocities, defending each in turn. When concentration camps were built in South Africa, for white Boers, he said they produced “the minimum of suffering”. The death toll was almost 28,000, and when at least 115,000 black Africans were likewise swept into British camps, where 14,000 died, he wrote only of his “irritation that Kaffirs should be allowed to fire on white men”.

…

As Colonial Secretary in the 1920s, he unleashed the notorious Black and Tan thugs on Ireland’s Catholic civilians, and when the Kurds rebelled against British rule, he said: “I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes…[It] would spread a lively terror.”

It’s understandable, then, that one very serious argument in favour of a flag change is to rid the New Zealand flag of the Union Jack. Not only is it the flag of another nation (the United Kingdom) but, for many people around the world, it is a bloody and oppressive symbol.

It’s important to remember that at the time Churchill carried out these actions and made these comments – and this is by no means ancient history – Britain was not alone in shoring up the power of its Empire.

New Zealand and New Zealanders played their part and, to date, have never formally resiled from that position.

Did New Zealand become a sovereign nation state by an act of rebellion against this imperial power?

Did it become a sovereign nation by protesting and fighting for its independence for decades and forcing the imperial power to relinquish it (as did Ireland, India and many African countries that were once British colonies)?

Did it argue forcefully in global fora against British Imperialism?

No, it didn’t.

And it doesn’t.

Instead, New Zealand became a sovereign state via becoming a dominion (with Britain’s blessing) and then (once again with Britain’s blessing) graduating to ‘full’ statehood.

More to the point, all along, New Zealand and New Zealanders directly aided Britain in its imperial efforts – think the Crimean War, think the South African (Boer) War, think the Malaya Campaign.

Yes, even the Crimean War – Charge of the Light Brigade’ and all that. New Zealanders were there.

And that Empire-supporting tradition didn’t stop at the Crimea.

There’s been a lot of discussion over the silver ferns carved on the gravestones of New Zealand soldiers over in Europe. But that distracts from the most important point to remember: Think about that phrase for a second: ‘over in Europe‘?

The truth is that New Zealand soldiers were only ‘over there’ to help Britain, and the rest of its Empire, fight an imperial rival. And, as an ex-soldier who is actually a supporter of changing the flag pointed out recently on RNZ National Morning Report: The coffins of those soldiers from World War I and World War II were not draped in the New Zealand flag – they were draped in the Union Jack.

If I heard him correctly, that was by Government decree (presumably the New Zealand Government).

Here’s the interesting audio of the half hour of debate. The point about the draping of coffins in the Union Jack is mentioned about 8mins 45secs in:

The reason for that practice of using the Union Jack on the coffins is obvious – they were fighting an imperial war, or at least a British war, and everyone knew it. They were even often under British command or directly served in the British military.

Silver ferns on their gravestones completely glosses the fundamental point: it was the Union Jack under which they fought, died and were buried – the latter by their own government’s decree.

All along, New Zealand and New Zealanders ‘did their bit’ for the so-called ‘Butcher’s Apron’. If there is innocent blood on that apron then New Zealanders, albeit indirectly (I hope), helped put it there.

That, I’m afraid, is the history of this independent nation state called New Zealand.

No doubt irritatingly for some, that is also one of the main reasons that New Zealand still has the Union Jack on its flag: New Zealand has never formally rejected – or ejected – its colonial past.

And that’s more than a formal or logical point – it’s supported by evidence of the country’s current behaviour on the world stage. (Moreover, New Zealand has its own internal legacy of colonialism with which it is still very much struggling – but I won’t detail that here as there are others who know far more about the history and current status of that struggle than I do.)

The colonial ‘past’ is still very much with us, and not just because of Royal Tours and Prime Ministerial visits to Windsor Castle.

There’s presumably also the direct support for, and pride in, that colonial past and origins that some New Zealanders still feel. How great is that support?

The recent upsurge in Royal Tours, the apparent popularity of the ‘young Royals’ (according to the Prime Minister) and the reinstatement of Knighthoods and Damehoods have been pointed out by others as indicating, at least, a remarkable tendency for New Zealanders to tolerate reminders of colonialism and imperialism. This is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than by the ‘Dames and Sirs for Flag Change’ group who have already been extensively lampooned and skewered:

Then there’s the shameless audacity of the acolytes. Exhibit A, Dame Jenny Shipley, fulminating in the campaign video that she “doesn’t want her grandchildren growing up under a colonial flag”, despite happily hoovering up a “colonial” damehood. Self-serving hypocrisy at its most majestic.

But not only do many prominent New Zealanders seem happy to accept titular honours that are nothing if not vestiges of imperial pretension, and not only do we have a happily royalist Prime Minister but, far more to the point, we also have ties that are anchored down in the bowels of the enduring ‘deep state’.

The best place to look to find New Zealand’s enduring identity as a nation in the ‘family of nations’ is in the fundamental relationships we, as a nation state, maintain with other countries.

What kind of ‘fundamental relationships’ do I mean? Trade might be thought to be one ‘relationship’ but is it ‘fundamental’?

Who we trade with changes over the course of history and presumably will continue to change on into the future. These are not stable relationships over time (unless they are, for example, colonial or imperial ones).

Obviously, there is little point in a flag trying to reflect our trading relationships in any specific manner (i.e., which other nations are important to us in terms of trade). Today it might be Australia, tomorrow the US, the day after South East Asia and, after that, who knows?

So if not trading relationships then what other relationships? How about ‘geography’? We are ‘in’ the Pacific so how about connections to the Pacific and its nations? How about some reflection of just how we are ‘in’ the Pacific? Sounds promising.

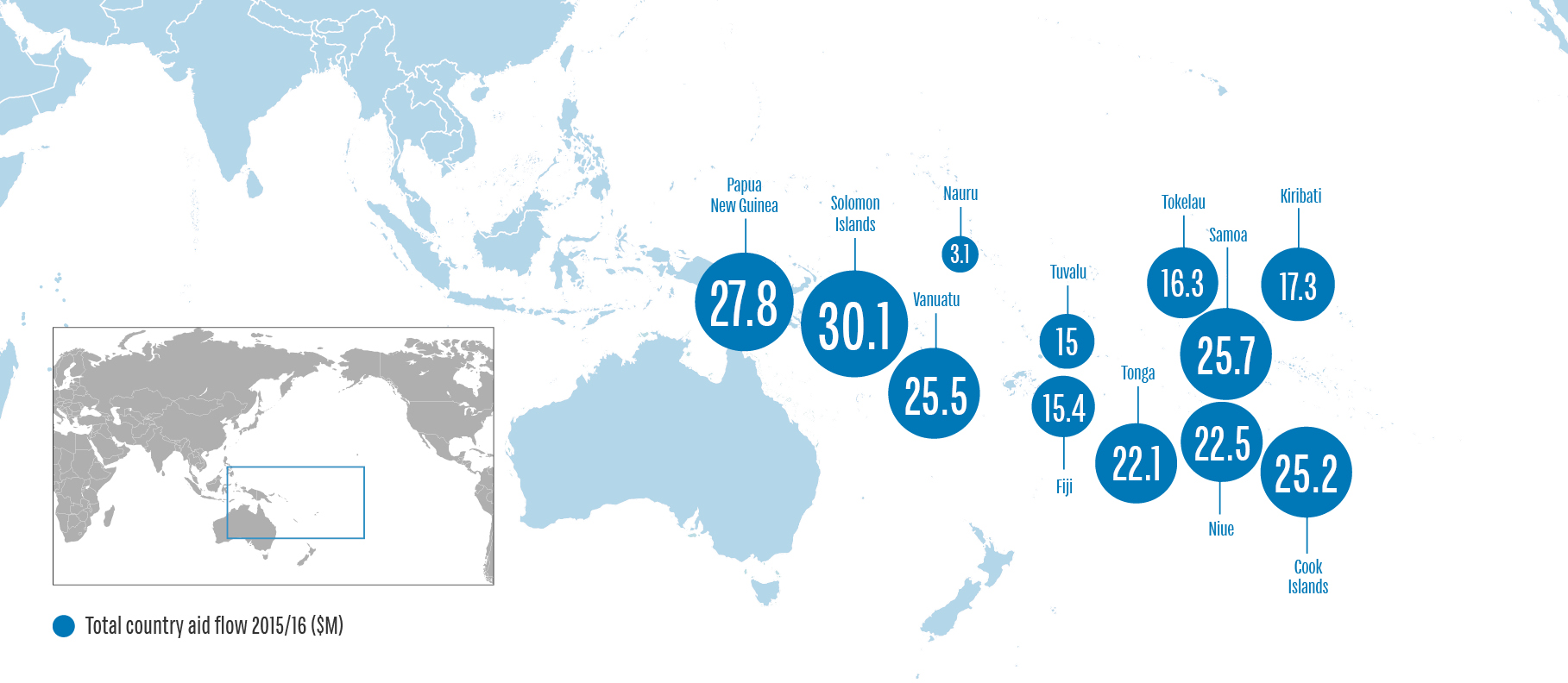

Interestingly, many of those links – especially the strongest ones – come out of New Zealand’s colonial past and role. This map shows the focus of New Zealand’s overseas aid:

NZ Aid and Development Funding in the Pacific 2015-16

The Solomon Islands (former British Protectorate) receives the most (presumably because of the Defence Force deployment) followed by Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Vanuatu, the Cook Islands and Niue.

Papua New Guinea was a British colony and was handed over to the new Commonwealth of Australia in 1905. It received independence from Australia in 1975 but remains the main recipient of Australian aid (and, as the map shows, the second highest recipient of New Zealand aid).

Western Samoa was once a German territory but New Zealand sent in an expeditionary force during WWI and remained as de facto government until 1962 (the history of Samoa in the 19th and 20th centuries is a fascinating epic of colonial rivalry).

Vanuatu was an interesting case of a colonial ‘joint venture’ between the French and British (The British-French New Hebrides).

The Cook Islands and Niue are states in “free association” with New Zealand and that interesting set up is based, of course, on colonialist origins and the ‘responsibilities’ that continue to today.

Fiji was also a British colony (after 1874).

This at least provides a strong clue to the more ‘fundamental relationships’ New Zealand has with other nations and the basis for those relationships.

Then there’s the fact that the military remains intimately enmeshed with the forces of our ‘allies’ – principally, Australia, the United Kingdom and, of course, the United States – and this despite the suspension of ANZUS after the nuclear free legislation.

These military ties involve the usual Anglo-Western suspects. And they’ve been the usual suspects for a very long time – right back to the origins of the colonial state called New Zealand.

There was disturbing evidence of the extent to which this may have affected the behaviour of the military in the recent deployments in Afghanistan, the Persian Gulf and Iraq. Nicky Hager’s book ‘Other Peoples’ Wars’ claimed that:

the Navy and Air Force escorted and protected the Iraq invasion force despite instructions by the then Labour-led government not to get involved in the conflict

Having read the book I can vouch that there are many examples described, and plenty of evidence presented, to suggest that maintaining and extending ‘close ties’ with the UK, Australian and US forces was not merely some occasional concern of significant elements of the New Zealand military but an ever-present objective. Like some self-correcting gyroscope, the military apparently has an inbuilt mechanism to compensate for ‘momentary’ departures from our true role in the geopolitical landscape.

This is no abstract point.

Considerable sums of money are involved in the defence acquisition budget. The upgrades and acquisitions made are often with an eye to ‘complementing’ the defence capabilities of these same allies.

For example, there’s the $200m recommended upgrade to the anti-submarine capabilities that briefly surfaced in the news (poking its periscope above the waves). In an interview on Morning Report on RNZ National, Labour’s Defence spokesperson, Phil Goff, had this to say about the proposed upgrade:

“I suspect that the reason that the government is going ahead is because they have been asked to go ahead with that capability by allied countries rather than our own evaluation.”

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he? But it turns out that, while in favour of the upgrade, Professor Robert Ayson of Victoria University’s Centre of Strategic Studies also sees one of the main advantages being its ‘fit’ with our “relationships” with our allies:

“the upgrades will allow New Zealand to maintain close relationships with the Australian and American forces”

Beyond the military, there’s also been interesting revelations about the relationships between our intelligence agencies and those of the same ‘Anglo-Western suspects’. The role of the GCSB in ‘Five Eyes’ is now part of everyday café chatter.

A succinct description of the cooperative group of intelligence services from the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand was given by everyone’s favourite whistleblower/ traitor, Edward Snowden:

The former NSA contractor Edward Snowden described the Five Eyes as a “supra-national intelligence organisation that doesn’t answer to the known laws of its own countries“. Documents leaked by Snowden in 2013 revealed that the FVEY have been spying on one another’s citizens and sharing the collected information with each other in order to circumvent restrictive domestic regulations on surveillance of citizens

Whether or not you’re in favour of or against such deep cooperation between New Zealand and these ‘traditional allies’ the existence of such cooperation stacks up in favour of the following claim: New Zealand’s role in the geopolitical landscape of the world is little changed from colonial times. Certainly, it’s a 21st century version of that role but it has shown remarkable endurance and consistency nevertheless.

It may well have been different if, for example, the Kirk government in the 1970s had continued in office. Who knows, New Zealand may well have joined the Non-Aligned movement, tossed off its ‘traditional allies’ and become a veritable Switzerland of the South Pacific.

But it didn’t. With the one ‘bump in the road’ of the nuclear free policy – and just why that happened at the same time as the advent of ‘Rogernomics’ is another interesting question – New Zealand has cleaved very closely to its longstanding role in the world, a role established at its colonial origins.

New Zealand troops, most recently, have been deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq – those ‘traditional’ sites of colonial and imperial ambitions and conflicts. New Zealand continues to act out its role of paternalistic Western patron in the Pacific (a role given new significance by the strategic wrestling between the US and China in that area).

It also has to be said that many New Zealanders are perfectly happen for today’s New Zealand to continue in those national footsteps, to continue to play that role.

But some don’t.

Many who would see themselves as ‘Progressives’ would be unhappy with that reality and would wish to change it, but reality it is.

And this is where I part company with many progressives who believe, when it comes to the flag referendum, that the answer is obvious: ‘Vote against the current flag and get rid of that bloody Union Jack!’

I think that reasoning is wrong for both moral and tactical reasons.

First, does this ‘aiding and abetting’ of British Imperialism get erased from this country’s past by changing a flag, by removing the Union Jack?

More importantly, would changing the flag by removing the Union Jack unambiguously mean a rejection of the often brutal reality of colonialism and Empire as some people want to believe it would? Many people who want to rid the New Zealand flag of the Union Jack clearly see it more as an assertion of independence than as a condemnation of the horrors of imperialism.

It may salve the individual liberal’s conscience to remove the Union Jack but does it do anything at all to change New Zealand’s continuing involvement in that project that remains markedly imperial in goals and manner if not in name?

Would removal of the Union Jack from the flag presage a new era of independent foreign policy, a new independence from the strategic geopolitical goals of its ‘allies’ (the UK, US and Australia)? Would it increase momentum for becoming a republic?

Perhaps we can look elsewhere for guidance or for a precedent to answer these questions. Are there examples of other nations striding out independently and rejecting imperialism and colonialism through a change of flag?

There is, of course, the case of Canada. It famously changed its flag by Parliamentary vote in 1965 and its national flag no longer bears the Union Jack. Part of the reasoning by one of the main flag change proponents concerned Quebec:

The suggestion was followed by Stanley’s memorandum of March 23, 1964, on the history of Canada’s emblems, in which he warned that any new flag “must avoid the use of national or racial symbols that are of a divisive nature” and that it would be “clearly inadvisable” to create a flag that carried either the Union Jack or a fleur-de-lis. According to Matheson, Pearson’s one “paramount and desperate objective” in introducing the new flag was to keep Quebec in the Canadian union.

Despite these very local reasons for change, hasn’t Canada nevertheless shown us the way to stand proud and independent and, in the process, to get rid of the ‘Butcher’s Apron’ (aka ‘Royal Union Flag’ or ‘Union Jack’) and its associations with colonialism and Empire?

With the adoption of the maple leaf–based National Flag of Canada in 1965, the role of the Royal Union Flag changed within Canada. On 18 December 1964, Parliament resolved that the Royal Union Flag would continue to serve as a symbol of the nation’s allegiance to the Crown and of the country’s membership in the Commonwealth. As a result, the Royal Union Flag can still be flown in Canada (alongside the national flag) at federal government buildings, on military bases, and at airports on particular days, including the Queen’s birthday, the anniversary of the Statute of Westminster (11 December), on Commonwealth Day (the second Monday in March), during Royal visits and visits from officials of the United Kingdom.

While there are no laws about the flying of the Canadian flag apparently there are some interesting good practice protocols:

When flying the flag, it must be flown using its own pole and must not be inferior to other flags, save for, in descending order, the Queen’s standard, the governor general’s standard, any of the personal standards of members of the Canadian Royal Family, or flags of the lieutenant governors.

Far from being a lesson in how ‘successful’ a change of flag can be in rejecting the brutality of empire – or even in asserting independence and distinctiveness – the case of Canada is much more an object lesson in how a superficial change in image can disguise a much deeper continuity. Continuity of the same old institutional arrangements, the same old ‘bending of the knee’, the same old tacit support for colonialism and imperialism – that is, for the same old same old.

Similarly, New Zealanders, as a national collective, have to date never shown a desire to cast off the chains that connect them to an imperial and colonial past to the extent that they have been willing to support a fully independent and self-determined ‘re-invention’ of their statehood.

Some individuals have – and do – of course. But that’s not what I mean. As a nation we haven’t.

I think the reality and truth about countries should matter; and they should particularly matter to those who see themselves as progressives. The moral imperative, so the saying goes, is to ‘speak truth to power’.

To go for a change of image before there is a change in reality is not so much speaking truth to power as it is an acquiescence to power and its desire for us to drink the kool-aid of fantasy and image, and in that way diffuse and defuse complaint and resistance.

There is, in my opinion, far too much focus on image in today’s – largely neoliberal and commerce-soaked – world. Image confuses and distracts; it (temporarily) soothes the worried brows and anxieties this world generates; it deludes, dissipates and placates resistance.

Progressives, of all people, should seek to gain actual progress in the state of the world – and should do all in their power to remind others of the continued need for that progress to be made. They should seek to present the world as it is – not claim that it is already as they would like it to be.

That brings me to the tactical point.

Second, if the aim is to ensure actual progress in creating a truly independent nation state out of this country then it would be wise to store up, or even increase, what energy and momentum there is for change.

It seems clear that some people want to remove the Union Jack purely because they believe New Zealand shouldn’t have ‘another country’s flag’ on its flag. It’s about independence rather than rejection of what the Union Jack might symbolise about imperial and colonial brutality.

That means that, if the flag were to change in this referendum, those people would have been satisfied. So far as I can see there is no reason to suspect that such people would automatically support other changes. Some may support becoming a republic (e.g., Jim Bolger but not John Key). But would they support substantive changes in New Zealand’s geopolitical role (which I presume ‘progressives’ would wish to see)?

Tactically, that is, linking some substantive change to the ‘bonus’ of a flag change seems far more likely to gain broad support for the substantive change than would proposing such substantive change with a flag already expunged of the Union Jack.

Paradoxically, changing the flag now is likely to reduce the chances of substantive change later. For some reason, and as debate over the flag change referendum has shown, many people are remarkably motivated by the symbolism of flags. They can rouse their largely dormant political selves over a flag to an extent that I expect would not happen over more substantive political change.

The energy that some people clearly have for a change of flag should, tactically, be stored then harnessed to some actual change at a later date rather than be frittered away for its own ‘symbolic’ sake.

And progressives who support a flag change should think about how their own energy for change operates. Sure it is easy to ‘chew gum and walk’ at the same time (i.e., it is possible to both support a change of flag now and continue to work on more substantive change). But, almost by definition, those progressives who are exercised enough to argue passionately for the need to get rid of the Union Jack (and to get rid of it now!) because of its symbolic associations with imperialism and colonialism are clearly highly motivated by its presence on the flag.

If the Union Jack remains then such progressives will have an additional thorn in their side – a ‘burr in their saddle’ – that will help spur on their own efforts when pushing for more substantive changes.

To sum up; my view is that changing the flag through this referendum would both be dishonest (i.e., falsely represent New Zealand’s political arrangements and allegiances to the rest of the world) and anti-progressive.

Colonialism and imperialism are not just old, Victorian ways that no longer inform us about today’s world. They were – and are – massive global and historical events. To believe that their effects have so rapidly vanished from the face of the earth is naive. To believe that here in New Zealand we can no longer be characterised as a ‘colony’, that we no longer play any part in an ’empire’ seems to me to ignore reality.

Yes, technically those words no longer apply but in most other senses they still provide impressive insight into the ‘state of the nation’.

One day it may well be true that those notions no longer apply or provide anything but historical insight into the New Zealand nation state.

But until that happens, frankly, I don’t think New Zealanders deserve to jolly themselves along in some collective self-delusion by simply changing the design on a flag and believing that somehow that shows our ‘maturation’ as an independent nation state.

There’s more to maturity as a nation state – and to ‘national identity’ – than that I’m afraid.

Without some public debate that culminates in explicit constitutional change or a radical and explicit reorientation of the country’s role and behaviour in the world then the supposed ‘independence’ and ‘new identity’ that a change of flag expresses comes very cheap indeed – not even needing us to behave, ally or organise ourselves any differently.

If you want to change the flag, New Zealand, then I have one message for you – ‘Get some guts!’ and change the state you’re in.

In the meantime, stop messing around worrying about what dress you’re going to wear to the global high school prom just so you’ll be better ‘noticed’. Show some real maturity: Don’t choose a ‘false flag’.

This country and its people deserve far better than that.

Someone Else’s Wars was very easy to read, have you read the Great Wrong War by Elgridd-Grigg? It is a romping read, full of petty empirical behaviours of our troops, the ‘peaceful’ take over of German Samoa followed immediately by the killing of Chinese slaves/ indentured servants, falsely lured by our siren call of freedom and democracy.

Churchill the pugnacious little bigot was also behind the transfer of coal to oil of the British navy and the reason ‘our boy’s were in the middle east, not just Europe, WW1 being seldom talked about as the first war for oil. England’s first divisions once the war in Europe broke out was not to Belgium or France or Serbia, but to Basra in Iraq! And 100 years later ‘we’re’ going to Basra for oil again. Nuclear free has been a wash over veneer too, most of the serious where it counts international forums have had ‘us’ behaving like modern little Churchills undermining any progressive anti-nuclear arms treaties. When Prenderghoul removed the “welcome to wellington a

nuclear free capital” sign she did us all a favour.

LEST WE FORGET?

Lest we REMEMBER…

Hi WarlockofFiretopMountain,

(That’s a great name!)

No I haven’t read the Great Wrong War but will look it up in the library. It sounds like a really detailed and interesting account of New Zealanders’ involvement. Thanks for the tip.

Yes, we have Churchill to thank for overseeing the determination of the artificial boundaries that enclosed three ethnic groups in the same area – that was mentioned in one of the links in the post. It was also argued that his speeches during the war actually inspired ‘freedom’ movements around the world including in colonised countries – so there’s a case of some interesting ‘unintended consequences’ 🙂

Thanks again for taking the time to read my posts (I see that you’ve commented on an earlier post too!).

Regards,

Puddleglum

I have found it hard to agree with many of your posts but wholeheartedly support what you have said in these two ‘flag debate’ essays. We New Zealanders need an open, frank discussion as to who we are, what sort of nation we want to be and how we relate to the rest of the world. Sadly I suspect there are too many sectional interests who would wish to retain their present positions to make discussion possible…. I hope I’m being overly pessimistic.

Hi Minette,

Thanks for persevering with reading my posts given that you don’t agree with many of them. I admire that. Being open-minded enough to read what you suspect you may not agree with is an increasingly rare virtue.

I agree entirely with your point about the need for focused and serious discussions around just those sorts of questions. And, yes, there would be sectional interests trying to deflect or undermine those kinds of discussions. I think one approach, at Parliamentary level, would be a broad cross-party agreement that that kind of discussion is necessary. From that point politicians would have to be at arms length. Following that I suppose there would have to be something like a Royal Commission to look into the questions that it had been agreed needed careful consideration.

I wouldn’t be surprised that the reason the flag debate has become more heated and talked about than so many other matters that you might think would concern people more is because people are treating the flag debate as a proxy for just the kinds of discussions you mention but without articulating those issues very clearly (and getting distracted by questions of design, the All Blacks, etc.).

Thanks again for taking the time to read the posts. As ever, much appreciated.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Recently I was in Auckland for the TPPA demonstration.

The day a perfect flag flying day; hot, overcast, a strong breeze.

The protesting was epic. There were many, many flags. The most predominant was Tino Rangatiratanga or Maori sovereignty flag and then our current NZ national flag. The third prominent flag was the United Tribes flag. This flag, interestingly, contains all the same colours and many elements of our current NZ flag.

There were other flags and banners flying, some I did not recognize, but none were the new fern design. This is a signal, loud and clear, that the flag debate is intensely political. The people who don’t want TPPA don’t want the fern flag either.

The juxtaposition of those three flags tells us a lot about who are the TPPA protestors. Firstly, front and centre they are Maori because, as one man interviewed by John Campbell memorably stated, “it’s about sovereignty and Maori understand that.”

The current national flag was strongly flying, representing the older, largely Pakeha, heartland present in considerable numbers. There was also another group of people, multi ethnic, mostly younger and not obviously represented by any flag.

The flag referendum has come down to two opposing ideas:

There are those who hold to the conservative and perhaps imperialistic values of an older NZ, best represented by the RSA and ANZAC day. These support the current flag.

Then there are others who look to a global New Zealand, but are nationalistic in an almost a jingoistic way; all sports teams and “punching above our weight”. For this group the new fern flag is the ensign of choice.

But it’s not binary; there are other views of New Zealand not represented by either flag option.

Another vision, also nationalistic, at its heart the concept of sovereignty, is the Aotearoa of the Tangata Whenua and the Tangata Tiriti. That day in Auckland (to paraphrase the author, Arundhati Roy) I heard her breath in the wind. She lives, oh yes she lives!

Hi janinechch,

Thanks so much for the comment.

I deliberately left out of my post any discussion of the ‘internal’ aspects of our past and present encounter with our colonial origins. The history of how Maori are integral to our nation-statehood is fundamental to any answer to the questions ‘Who are we?’ and ‘What is New Zealand (Aotearoa)?’

For those with ‘eyes to see’ – and as you highlight -there’s an interesting juxtaposition in time of the flag referendum and the conclusion/signing of the TPPA. One is an expression of proud uniqueness and contrast to other nations; the other is acceptance of a borderless blurring of New Zealand/Aotearoa into a global arrangement of capital.

Strange days indeed.

Thanks so much for taking the time to lay out your insights and thoughts. Much appreciated.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Strange days? Yes.

The flag debate is surely a distraction over the process of the TPPA yet unintentionally (?) it has exposed some large divisions within our society.

Two large social groups, who currently favour the National party, are now on opposite sides of the flag debate. The discussions, turning to arguments, seem to largely focus on the war dead, sports stars, international branding, our whitewashed history and which flag would best represents this dubious picture.

Instead of a surge of unifying patriotism we’re getting a winner and loser situation.

On the side-lines, meanwhile, are other groups who don’t ascribe to any of this.

Momentous days? I think so.

Sometimes words are more than ‘platitudes’ they can become dangerous imbued with power. In this country sovereignty is such a word, especially if you prefix it with the word Maori.

This is because it’s not ‘feel good’ or a “vacuous snippet” (as per your discussion on the word cloud) and more than, an “expression of proud uniqueness and contrast “it is a material condition.

For the colony sovereignty is always revolutionary.

Dark days ahead.

“For the colony sovereignty is always revolutionary”

An excellent line – and, when you think about it, almost true by definition. And I agree that words are not necessarily just ‘platitudes’ or ’empty vessels’ signifying nothing. They can crystallise the realities of a situation.

The flag debate is the ‘sovereignty’ debate you have when you don’t have a sovereignty debate – it fills the space.

I think you’re right that it has devolved into some kind of rather mean-spirited sporting competition of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. To me that’s indicative of the fact that it has no real substance and yet it’s having all sorts of anxieties and interests projected into it just because of that lack of actual substance.

Regards,

Puddleglum

To include some of the comments above too, New Zealand has no real Constitution (you know, human rights, liberty, equality etc and stuff), the last review deeming it unnecessary, yet, as I’m reading Jane Kelsey’s FIRE Economy at the moment there has been an ACTUAL concerted effort historically up to today (from the Business Roundtable and the like) to install an ECONOMIC Constitution, of which one of the next steps is the TPPA. In many ways this last 30 years has been a complete success for capital and a highly risk tolerant approach that leaves customers, citizens and consumers with the burden and costs of financial miss-adventurism.

I maintain the Washington consensus and neo-liberal Rogernomic experiment was NZ’s 2nd colonisation and that the union jack should either be replaced with the stars and stripes, or they should be added below the jack to show our enthrallment to both the City of London and Wall Street.

Likewise Waitangi day celebrations could be shifted to the steps of the Reserve Bank and culminate in a ritual of still beating hearts of children dying of rheumatic heart disease ( a disease of poverty that NZ leads the OECD in, and that barely existed before the 1980s here) are torn out in Aztec fashion to appease the Invisible Hand and guarantee market stability for the next financial quarter.

But the question still remains, what flag to fly at such a patriotic and yet maternally fertile event?

Due to the cross-border existence of Trans-nationals a naval ensign or pirate flag could be appropriate, but historically most pirate ships were run democratically, with captains being unelected as often as elected and all aboard sharing equally in the proceeds, they escaped brutal conditions on both Merchant and Naval vessels with capital punishment for minor infractions commonplace; so a Jolly Roger is actually a symbol of democracy and freedom. Maybe a five armed Swastika made from Silver ferns with an eye at each end to symbolise the ever vigilant anglo-saxon club we work for…?

More on Churchill, he made sure the British invested in the to be fledgling British Petroleum company as they had divided the middle east with the French into countries whose borders ran between pipelines and oil carrying railway lines, the map has barely changed. Of course, the yanks felt left out (which they were) and the rest they say is history.

Lest we Remember…